On May 29, 2022, suspected Cameroonian separatists — the Ambazonian rebels popularly called the ‘Amba boys’ — attacked Obonyi II, a village in south-west Cameroon, leading to the loss of over 20 lives, with scores injured and displaced, and properties destroyed.

The attack was one of many carried out in connection with an ongoing Cameroonian civil war — the Ambazonia conflict or the Anglophone crisis. The crisis, which began in late 2016, stems from agitations from the country’s English-speaking south-west and north-west regions asking for separation from the eight French-speaking areas. They are demanding a new country — the Federal Republic of Ambazonia.

These warring regions border the Nigerian states of Cross River, Benue, and Taraba, which are now witnessing spillovers of the conflict. However, the exact location of the attack — whether it occurred in Cameroon or extended into border communities in Nigeria — remains contentious due to misleading information spread by some mainstream media, social media users, and influential individuals.

The attack of May 2022 for example, was reported to have spilled over to Boki, one of five local government areas in Cross River that borders Cameroon.

MISLEADING REPORTS AND VIDEOS OF THE ATTACKS ON NIGERIAN TERRITORIES

Several media outlets and blogs reported the Cameroonian attack on Nigerian territory in Bashu, a border village in Boki on May 29, 2022. Social media users on Facebook and X were also involved in sharing posts about the alleged attack on Nigerian territory.

Using an open-source intelligence tool, “Who Posted What?”, with the keywords ‘Ambazonia Boki’ and ‘Ambazonia Nigeria,’ over 340 Facebook posts were found between May and June 2022, on the alleged attack on Boki.

A Facebook user, Princewill Chimezie-Richards, alleged in a post that Bashu and Danare — another border village in Boki — were attacked simultaneously that day. The post generated engagements with 84 likes, 21 comments, and six shares.

Four other Facebook pages, Princewill-Chimezie Richards with about 10,000 followers, Princewill Chimezie Richards with 6,000 followers, Sunrise Daily TV with 107,000 followers, and Biafra Nations League with 38,000 followers — all linked to the same person — also published reports of an attack on Bashu and Danare.

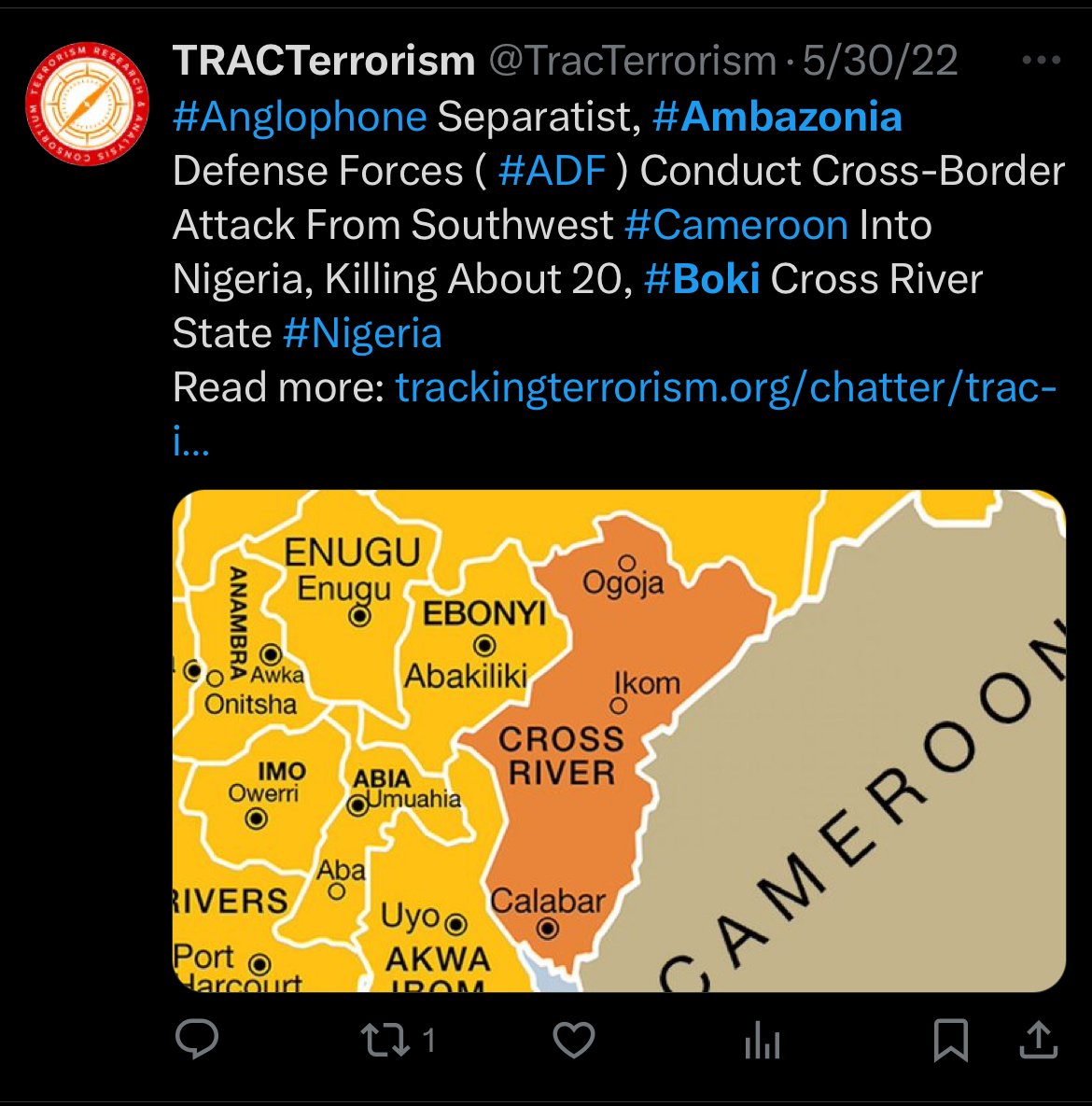

The alleged Bashu attack was also shared on X by several accounts, including TRACTerrorism, a global terrorism research and analysis consortium with over 47,000 followers.

Uncaptioned and misleading photos of armed militias were also used to portray the alleged attack by Ambazonian rebels on Bashu.

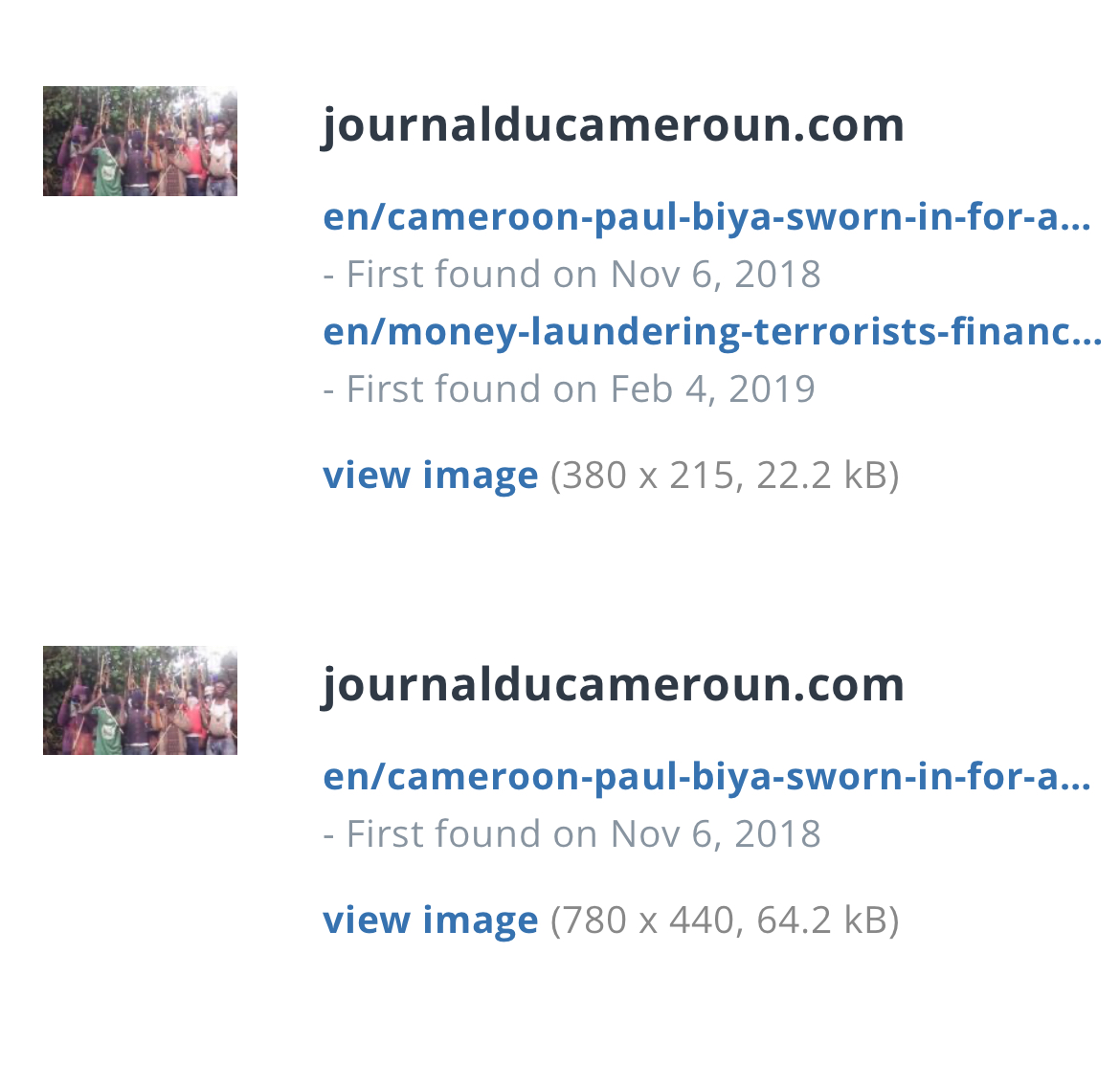

One of the photos showed armed militias with nose masks in front of a mud house. One of them had a cell phone. A reverse image search using TinEye revealed 75 matching results. The results were filtered to show the oldest reports where the photo was used and a BBC story from August 31, 2017, about Muslim refugees in the Central African Republic, was found. However, the BBC took down the photo on September 2, 2017, as seen in a footnote contained in the story, saying the previous image was incorrectly captioned.

Another photo showed armed men in front of trees with guns. Some had their faces masked while others wore sunglasses. TinEye found four results, with the oldest being November 6, 2018, in JournalduCameroun.com, a Cameroonian French publication. These findings proved that none of the photos used emanated from the alleged attack of May 2022.

A careful study of all published stories and social media posts about the attack found a recurring name: Cletus Obun, a former member of the Cross River state house of assembly and, at the time, an aspirant for the house of representatives for the Boki/Ikom federal constituency. He was cited as the source who confirmed the attack.

When a phone call was put across to him, he confirmed granting interviews on the attack and stood by his words.

“There was an attack on a nearby Cameroonian village to Bashu and the villagers from there trooped into Bashu. So when the rebels saw this, they thought some of their members had run into Nigeria and they chased them into the village and started to attack people,” he said.

However, on May 30, 2022, Irene Ugbo, the state police public relations officer, spoke to journalists and refuted claims of an attack on any community in the state by Cameroonian separatists.

Similarly, the Nigerian Army dismissed claims of an attack on Bashu through its Facebook page, saying its troops from Danare went to the community when they heard of an invasion by Ambazonian rebels but later discovered it was a false alarm.

Onyema Nwachukwu, director of army public relations, had said two Cameroonian villages — Obonyi II and Njasha— were those attacked. The mention of a second place, Njasha, raised questions as Germany-owned Deutsche Welle made a post about the attack on June 1, 2022, saying it took place in Obonyi II and that at least 24 lives were lost. There was no mention of Njasha.

A Google search with the keywords ‘Njasha Cameroon’ was conducted and all results were those linked to the statement by the Nigerian Army. For better results, Google Advanced Search was used to search for the keywords and the results were the same.

The reporter also tried mapping Njasha on Google Earth Pro, Apple Maps, and OpenStreetMap, and none of these tools yielded any results. However, upon rigorous research, the reporter found a place in Cameroon called Njassa, which could be where the Nigerian Army was referring.

Njassa is located in Cameroon’s Francophone Western region which is not affected by the Anglophone conflict. With this, it can be concluded that the Nigerian Army may have misinformed the public while trying to debunk false information.

A VISIT TO BASHU, NIGERIA

To uncover the truth about the attack, the reporter, in May 2024, visited Bashu, the border village where the attack allegedly took place.

“Road to the village bad well well. E get some places where wuna go drop from bike use leg waka,” Peter (pseudonym), a motorcyclist and fixer said, warning the reporter about the terrible state of the road to Bashu. A second passenger, a young man in his early 20s, sat behind the reporter.

The road, at the time of this story, was in a deplorable state and [passengers] had to dismount from the motorcycle at different points and walk. On one of such stops, the reporter engaged the second passenger in a discussion and discovered he was a Cameroonian vigilante returning home via the border road in Bashu.

“Amba Boys de worry my village, Obonyi, for Cameroon. Me and other young boys for my village don become vigilantes to protect our village. Sometimes we de cross come Nigeria to do business and see our family here,” the young man spoke in pidgin with a Cameroonian accent.

His statement revealed how anyone, including local vigilantes from Cameroon, freely crossed into Nigeria territory. Despite being a road leading to a border village, no security checkpoint was seen during the half-hour journey through a dense forest with no internet reception.

“We don reach, na the village be this,” Peter said, informing the reporter about the arrival at Bashu, a nucleated Nigeria village with a population of over 3,000 people. Nearly half of them are Cameroonian refugees who fled various attacks by Ambazonian rebels.

The first stop at Bashu was a primary school where the chairman of the community, Moses Abang, works as vice principal. He was asked if the claim of an attack on his community in 2022 was true and he debunked it. He was also asked if the village had ever witnessed an attack by Cameroonian rebels. “They have never crossed the boundary to our community and they can never try it,” Abang responded.

Three indigenes of Bashu who have been there since May 2022 were interviewed individually and they all gave responses that corroborated what Abang said — Bashu was not attacked.

After the interviews, the reporter was led to an uncompleted building to speak with two Cameroonian men who witnessed the attack on Obonyi II.

“This story so wey me I wan talk, tears wan comot from my eyes. Na 29 May e happen for that 2022 for Obonyi II. Them Amba boys enter around 8 am and them operate for over 10 hours. Them kill people, burn houses, them turn rich men to poor men. Them shoot me and I come de unconscious,” one of the young men, Keto, recounted in Cameroonian pidgin, as he carefully sorted out dried marijuana leaves.

Both men were asked if there was a spillover of the attack into Bashu. “Na for my village for Obonyi II. Them kill my father. My father don die. Them no enter here,” the second young man said, refusing to mention his name.

Three other refugees were interviewed separately and they all gave similar accounts of the incident. Each refugee was asked to describe the road leading from Obonyi II to Bashu and how they could tell if they had entered Nigeria’s territory. They all said immediately they crossed a certain stream and reached a border stone, they had entered Nigeria’s territory.

VISIT TO OBONYI II, SOUTH-WEST CAMEROON

“We no fit go there, e dey too dangerous,” the fixer said, citing security concerns after being asked by the reporter to go on a trip to the border. He eventually agreed after much pleading. The essence of the trip was to take photos and get coordinates of the area.

Just as before, there were no security checkpoints on the border road, only a small shade stood about four minutes from the village where a man described as an immigration officer sat outside. All one had to do was pay him the sum of N500 or N200, depending on the level of relationship with him, and one would be allowed to pass.

About 20 minutes later, the motorcycle stopped in the middle of another dense forest, just before a big stream and borderstone. “The attack been happen for the village wey dey over there, for Cameroon territory. E no happen this side for Nigeria,” the fixer said, pointing his right index finger across the stream where an untarred road stood. “But we no fit cross go there because e too risky,” he added, referring to the possibility of coming in contact with the Amba Boys and risk getting attacked or worse, killed.

Crossing over and taking photos to get coordinates was one major way to establish what country the attack happened. It took another round of pleading for the fixer to accept to cross with the reporter. Photos were taken in the stream and on the untarred road across, using an iPhone with location turned on.

The photos were analysed on Apple Maps. All photos taken before the stream when coming from Bashu, showed Boki, Cross River State, Nigeria, as the location. However, photos taken inside and across the stream had south-west Cameroon as the location. The coordinates of the photos were also copied to Google Earth Pro and the result was the same. This proves that Cameroon’s territory was attacked on May 29, 2022, not Nigeria’s. Victims had to cross the stream to get to Bashu.

The next day, the reporter visited Danare and interviewed residents who all denied an attack on the community on the said date. All evidence proves claims of an attack on Nigerian territory on May 29, 2022, were false.

INCORRECT NUMBER OF DISPLACED PEOPLE IN BELEGETE

About four hours away from Bashu is Belegete, another border village located in Obanliku local government area of Cross River state. In December 2023, the community was invaded by suspected Ambazonian fighters who killed a chief, burnt houses, injured many, and displaced the villagers. Since then, events surrounding the attack and the lives of displaced persons have been marked with fake and misleading information.

Before the attack of December, over 100 Cameroonian refugees sought refuge in Belegete otherwise spelt Balegete, said Sunday Egunu, a youth leader from the community.

Media outlets reported that 31 people, including the late chief, were abducted during the attack. Both outlets cited Peter Akpanke, the member representing Obudu/Bekwarra/Obanliku federal constituency in the house of representatives, as the source of the information.

The Cross River ministry of humanitarian affairs, in a Facebook post, also said about 30 people were abducted from the community. To verify this claim, the reporter visited the Obudu Ranch Resort in Obanliku to speak with displaced villagers currently taking refuge in old houses and relying on aid from the state government for survival

Witness accounts and official documents made available to the reporter proved that the claim of 31 people being abducted is false as only 13 people, including the late chief, were abducted. And while others have been found, only four are still missing. The villagers say the four are being held hostage by Ambazonian rebels but this claim cannot be confirmed.

Although Belegete as a community was invaded, attacks happened in four out of nine villages that make up the community. These are villages closest to the Cameroon border. A chief from one of the villages confirmed this, requesting to remain anonymous.

On Facebook, media aides and supporters of Jarigbe Agom, the senator representing Cross River north senatorial district, shared copied posts of the senator’s support to displaced persons and stated that about 20,000 families have been displaced from Belegete due to the attack on the community.

This information was found to be false as Belegete has a population of less than 10,000 with those displaced at the ranch a little over 1000. Egunu and the chief confirmed this.

ABSENCE OF SECURITY AND POROUS BORDERS FUELLING FAKE NEWS IN COMMUNITIES

While the attack on Belegete happened in December, villagers who were farmers remained displaced and unable to return to their community due to the absence of security presence and failed promises of the state government to facilitate their safe return home.

Besides Danare where troops of the Nigerian Army are stationed, there is no army presence, police station, or security checkpoint anywhere around Belegete or Bashu. The only police station at the ranch which should have been the closest to the people of Belegete has been abandoned for several years.

Just like Bashu, there is no accessible road to Belegete from the ranch except a footpath which is a walk of about five hours and involves descending and ascending the fierce mountains of Obanliku. An alternative road to the community is through Okwa, another porous border community in Boki. There is no security presence and the road is in a terrible state. It is only accessible by bicycle and motorcycle with passengers forced to stop at different points to walk on foot.

The presence of these porous borders worsened by bad roads and economic neglect from the federal and state governments has enabled mischievous actors to spread fake news and misinformation about spillovers of the Ambazonia conflict in Cross River border communities.

Villagers also live in fear knowing how easy it is for Cameroonian rebels to invade their communities if they decide to. A 2019 study published in the African Journal of Politics and Administrative Studies found that Nigeria’s porous border is the underlying factor that precipitates infiltrations of terrorists and bandits. According to Risk Control Nigeria, the Cameroon-Nigeria border is relatively porous and is often used to smuggle weapons and ammunition.

BIAFRAN SEPARATISTS SHARING FAKE NEWS OF ATTACKS ON NIGERIAN TERRITORIES

Since the Ambazonia conflict began, numerous social media accounts linked to supporters of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), a Nigerian separatist group, have been involved in sharing fake and misleading information about attacks by Ambazonian rebels on Nigerian territories — including those in Cross River State — which they call Biafra territories.

Chimezie-Richards who shared the news of an alleged attack on Bashu and Danare is one of many pro-Biafra and pro-Ambazonia agitators using social media platforms Facebook, X, and YouTube to share false and misleading content capable of instigating unrest and manipulating public perception. His social media posts about the attack put residents of Cameroon border communities as well as refugees in Cross River at risk.

A 2021 report by the BBC revealed how Ambazonia Defense Forces (ADF) in Cameroon had built an alliance with IPOB in Nigeria. Chimezie-Richards, in several Facebook posts, has demonstrated his support for Ambazonia rebels and acknowledged having a close relationship with its leaders.

In a video shared on Facebook, Chimezie-Richards called on Otu Bassey, the governor of Cross River, to expel Cameroonian refugees whom he called ‘animals’ from Nigeria if they posed a security threat, or his men would take matters into their hands.

On X, Richards has over 2000 followers, and many of them have Biafra-linked usernames.

Commenting on the dangers of fake news, Promise Mboh, a Cameroonian journalist and researcher on the Anglophone crisis, said: “Hateful comments and fake news about the Anglophone crisis have caused the crisis to go deeper and escalate because most times they incite a lot of pain and hatred towards various regions and tribes affected by the conflict.”

Remmy Falade, a senior technologist at the Information and Communication Technology unit of the University of Calabar, said digital technology and social media platforms have made it easy to spread misinformation.

“Innovation in digital technology, especially the rise of social media platforms has made it easier for people to spread misinformation,” Falade said.

“Receivers in most cases do not verify the authenticity of what is shared on social media. Some of these platforms pay users through monetization and because of that, many people have gone out of track by spreading fake information thereby creating a misinformed society.”

Although Section 59 of Nigeria’s Criminal Code Act prohibits the publication of false news with the intent to cause fear and alarm to the public, nobody has been arrested for sharing fake and misleading news linking the Ambazonia conflict to border communities in Cross River.

“We have not been able to arrest anybody because misinformation doesn’t come from one direction. The information is shared by one person and the person passes it to the next. It spreads like wildfire and you cannot get hold of one person to arrest,” Ugbo, police PRO for Cross, said.

This reporting was completed with the support of the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development and the Open Society Foundations.